Responding to Young People's Fear of School Violence

Yesterday, I wrote a different post in a moment of heart-wrenching fear. My daughter was in lockdown, a block from an active shooter situation. Her dad and I texted with her until her phone died. It was a harrowing three-hour experience. A man was killed. A family lost a parent, faculty lost a friend, and the world lost a brilliant scholar. This is the unimaginable, and I won't try to put words to it.

Today, I decided not to share the full post, because it was written in a moment of fear. I was reacting, not responding. My daughter's campus was barricaded. Police, SWAT teams, and armored vehicles lined the streets - and I couldn't get to her.

To acknowledge the very real experience in my community, I'm including a screenshot from my original draft:

I updated the post every 15 minutes with new developments. The building my daughter was in was one of the last to be evacuated. We live in a small town and the suspect was at large, so all 20 schools were in lockdown, including my son's high school. It was our first day of public school.

The draft of my first post was an expression of raw fear, including the headline: "First Day of School: Lockdown." I was mad as hell. I'm still mad as hell. Young people, from kindergarten to college experienced TERROR yesterday. And not 10 students or 100 students, but tens of thousands of students. The college alone has 19,000 undergraduates. That doesn't include the 12,000 children in public schools, their parents, graduate students, campus faculty & staff, or anyone else involved.

Pivoting from reacting to responding

At 4:18 pm, we were given the "All Clear." My son went to get his sister (he wanted to)... I looked at my headline and thought, No. I'm not going to center this post around feeling fear. I'm going to center it around responding to fear. That's our work to do as parents and caregivers: moving from reacting to responding.

Parents, it is so hard to be immersed in horror and respond to our children in a grounded way. Yesterday, I was mostly reacting. I called my sister to tell her that my daughter, her niece, was okay, but in the process of telling her that she hadn't yet been evacuated from her building, I started bawling. It was, in part, a release from holding it together for three hours. Sometimes we react before we can respond... more evidence that we're human.

To manage to a powerful emotion like fear, it helps to break the thing we're afraid of into smaller parts. This dissecting, labeling, exploring, and understanding is how we practice Emotion Science. We can break the threat of school violence into pieces. It's usually:

- Unpredictable

- In the public eye

- Magnified in scope

- A nightmare scenario

- Personal

Taken together, those pieces add up to something that feels Very Big.

When I was a kid, we had fire, hurricane, and nuclear war drills. The nuclear drills were the scariest. But even those had nothing on active shooter drills. It's not like there were nuclear bombs exploding in nearby states or towns. Nuclear war seemed pretty unlikely and totally other worldly - like if a space alien landed in your school parking lot.

But school shootings feel up close and personal. They could involve a classmate or a neighbor. They revolve around emotions like rage and hurt. And that makes it a lot harder to get distance on the threat.

Another thing that's different now versus my childhood: the 24-hour news cycle. I didn't have to see mushroom clouds on my feed every 90 seconds. We live in a time when all things are public, and the worst things are magnified. That's not to say that school violence isn't very real, but it looms largest in our minds and in the national conversation.

The Terror(ism) of School Violence

Although even one school shooting is too many, statistically they remain rare. Mass school shootings are rarer still. HOWEVER, school shootings feel all too common to students (and consistently anxiety-inducing). School and workplace shootings have the same effect as terrorism. Even though they are not terribly likely, they spread fear just the same.

Here is her response:

What she's trying to tell me is, "Diluted statistics like these minimize the reality of gun violence in the youth population" and "For my generation, the threat of gun violence feels magnitudes larger than what statistics can capture."

When we're talking to our older kids, teens, and young adults about things that deeply impact them, it's a conversation, not a monologue. Sometimes, it's a very uncomfortable conversation that pushes us (as parents) into unfamiliar territory. If we can find a way to be okay with that discomfort, we can learn from their experiences and insight - and better support them.

Support starts with listening

The first line of support is to listen deeply and empathetically. We don't need to ignore our own anxiety, we just need to set it aside while we try to absorb what it's like to be a young person attending school in the 21st century.

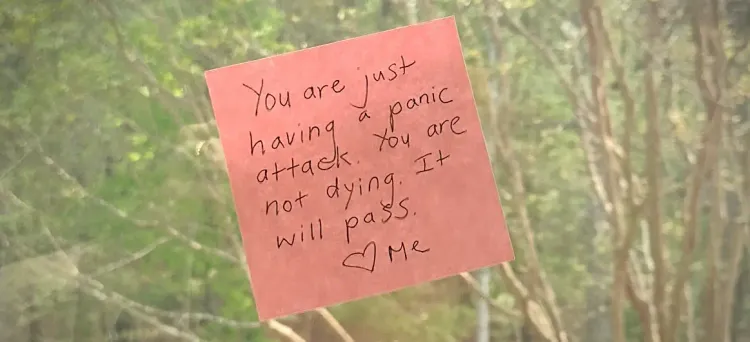

My daughter shared this story after she arrived back home and we sat around the dinner table together, debriefing.

For three hours, this was the only "official" information they had:

Stories like this one are terribly difficult to hear. They are heart wrenching. But we can be brave enough as caregivers to hold space for our kids to pour our their words and feelings. When they are allowed to do this, they not only feel heard and seen, but they begin to sense-make through story.

That doesn't mean senseless acts of violence suddenly make sense. It means our children can feel our support as they sort out their emotions and their experience of the senselessness. They can narrate the fear instead of having the fear narrate.

Listening is just one way we can help our kids and teens manage fear of school violence.

Here are other ways to offer support:

Right after a threat, we can avoid...

- Minimizing our child's feelings or experience.

- Talking at them rather than listening.

- Reacting (from our own fear/anxiety).

Instead We Can...

Provide our full attention to our child's experience, even if it's just validating the emotional experience of fearing school violence might happen.

- Listen deeply with empathetic body language and facial expressions.

- Help kids sort out their feelings. This starts with trying to identify what it is that they are experiencing - anger? Sadness? Grief? These emotions come clustered together and change moment to moment.

- Help them "story talk" their emotions and experience. "Story talk" is a Hawaiian expression for talking through feelings and experience in a narrative way, telling the story of what happened and how it affected you.

- Validate their emotions and experience. This might be the most impactful thing you can do. Validation might sound like, "I understand why you have nightmares about school shootings. It's so hard to live with fear." Then don't offer a "but" or an argument for why they shouldn't feel that way. Just leave it at that - pure validation.

- Respond instead of react. All of the above suggestions help you to thoughtfully respond to your child rather than emotionally react.

- Stay connected to them. Have family dinner. Take them on a parent-kid outing. Encourage them to connect with helpful friends.

Later We Can:

- Reassure your child/teen adults are working to improve safety (while acknowledging, especially for older kids/teens, that we have a ways to go).

- Seek the help of a counselor or other mental health professional when further support is needed.

- Continue to listen, help them sort emotions, validate, and help sense-make their experience (more on that in other posts).

- Stay away from news and other stressful content including social media (even short breaks help), and instead do something fun, restful, or helpful.

- Support them in taking meaningful action. If they want to sign a petition or march in the streets to demand more stringent gun laws, walk by their side. When they are ready, you can introduce ways for them to feel and be more powerful. This is how they grow their sense of personal agency, the feeling that what they do has impact.

- Help them fact check their emotions. If you feel your child/teen has some emotional distance on their experience, model "questioning a worry," "What evidence do I have to back up this worry?" "What are the facts?" We need to be very careful here to not sound dismissive of our child's emotional experience and to remember that school violence feels a lot like terrorism. We, as parents, can relate to how that type of fear creeps into our minds and hearts.

- Cope ahead - you and your child can collaborate on things within your control by creating emergency plans and filling resource gaps. For instance, you can have a failsafe method for reaching each other at any time. After debriefing with my daughter, we realized she needed a cheap portable phone charger to keep in her backpack. Stress thrives in "what if" scenarios. By leaving fewer unknowns ("What if I can't reach my mom?"), there are fewer spaces for fear and worry to seep in.

- Reframe hard emotions as friendly messengers. We can help our kids understand that emotions like fear and worry are (trying to be) protective. It's the mind & body's way of saying, "Hey! Look out!" If we reframe hard emotions, they become more manageable (less stressful and scary).

- Recognize that threat responses happen on their own time table. Sometimes we respond to a threat, or potential threat, immediately. Other times, we'll have a delayed response (could be days or weeks later). Your young person might "seem fine," and then weeks later start having nightmares. You can help by demystifying why this might be happening. You can talk with your child, and in conversation, draw connecting points to an earlier experience.

- Understand the sensory nature of traumatic experience. Help your child or teen understand too. During fight-or-flight, our nervous systems are wired to acutely take in sensory stimuli, register it, and file it away. This process is key to human survival. On the flip side, sounds and other sensory info experienced during a threat can send us back into fight-or-flight even when it is a lesser threat or no threat at all. ITS article here.

Look, I'm not going to lie to you. I don't always cope perfectly. I was scared (rhymes with) witless yesterday. And by evening, two hours after all clear, I was at the grocery store picking up my friends, Ben & Jerry.

We are all human, doing the best we can. This is hard stuff. I mean, this is incomprehensibly hard stuff.

Give yourself space and forgiveness to mess up and figure this out. Give your kid that space too.

We can get through impossibly difficult things when we feel supported.

Emotions aren't dangerous

We can help kids be curious about difficult emotions rather than see them as dangerous. Our fear won't hurt us. Our anxiety isn't the threat. It is our reaction to fear and anxiety that can feel harmful. If we can sit with these hard emotions without judging them or avoiding them, we can move through them.

That will mean listening to what those emotions have to say, and that's okay. If they aren't dangerous, we can respond to them and not react. That doesn't take away the threat of school violence, but it gives it less power. It's natural and understandable to feel fear about a possible shooting at school. But we don't have to be afraid of the feeling of fear itself. That's just our emotions trying to protect us. That's it.

It's okay to talk back to that emotion once you know it doesn't have anything new to say. But first, listen. Encourage your child to listen to what they are feeling with curiosity and compassion, but not with more fear.

Additional information

Parent Guidelines for Helping Youth after a Recent Shooting, from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network