Understanding the Sensory Nature of Threat

August 30, 2023 | A school shooting happened in my community two days ago. Although I leave the subject of trauma to clinical experts, it's clear that events like this reach so deep into communities that we need a wider circle of support. This post is to contribute to that conversation.

Disclaimer: The info shared here is not intended to replace therapy, but instead, to provide reflection and general strategies for helping kids process the sensory experience of threat. If your child has experienced trauma and needs mental health services beyond the scope of your care or non-clinical resources like this one, please seek the help of a mental health professional.

We live a few miles from campus, and my daughter is a college student at UNC. Like most parents in a community that has experienced school violence, I'm witnessing the direct aftermath of a school shooting. This includes reading posts of students' harrowing experiences, talking to faculty who attended the candlelight vigil for the professor who senselessly lost his life, listening to the experiences of my children held in lockdown for three hours, and processing through my own emotions. It's a lot. Too much.

With each day, something new surfaces that brings further awareness of what students and faculty experienced. Yesterday, my son showed me a video of the very moment that students heard the siren going off around the UNC campus.

I've heard this same type of siren bellow through our town to announce a tornado warning, and I can tell you - It's scary as hell. I'm talking about just the sound of the siren, and not the booming voice that accompanies it (which feels dystopian).

The Sounds of Lockdown

The TikTok (seen here) was recorded by Muhsin Mahmud, a journalist who just happened to be on campus that day. In his video, you hear him talking, and a few moments later, you hear the campus-wide alarm. As he notes the siren he looks around and says, "People don't seem to be reacting..." He has no idea why the siren is going off but he says, "Sounds like World War II."

A moment later, the reverberating voice of an administrator makes an announcement:

"ATTENTION: Armed and dangerous person. Go inside. Repeat. Armed and dangerous person. Go inside."

Video then shows students fleeing, most in absolute panic. The journalist films as he runs to a nearby building, up steps, then into an open doorway with barricades already in place and terrified students streaming in. It's stomach-turning to watch.

You can imagine how awful it was to be there, that alarm booming overhead, the sight of your fellow students running for their lives. And you can imagine that the next time students hear this alarm, the fear and anxiety experienced during that moment might return to them. Before the administrator made the announcement, students were calmly walking to class - even with the sound of the siren. Most, like my daughter, probably thought it was a weather warning.

The Threat Catalog

What happens with serious threats is that our brain catalogs all the sensory data accompanying them: sights, sounds, smells, and other sensations that can be used to identify future threats.

These "sensory threat alerts" are part of our evolutionary design. They are filed in our memory (the hippocampus, which is networked with the amygdala: HQ for fight/flight) so that we understand that the sight of a snake is cause to run, or that the smell of smoke is reason to have a look around (and maybe then run).

Something that, prior to a serious threat, might be viewed simply with calm caution can be "re-catalogued" or "upgraded" to MAJOR THREAT. This is when our nervous system takes over, because a major threat bypasses the prefrontal cortex (the thoughtful brain) assuming that there is NO TIME to lose in responding reacting.

For day-to-day living, being locked in reacting is harmful and miserable. It's only useful in the moment of real, specific threat.

Parents can provide support

To help your child process through a sensory-based fight-or-flight response (e.g., a certain sound activating fight/flight), ask them if they want to talk about what it was like during that sensory moment.

We can listen. By doing this, we open space for what our child is holding in. It's important to listen without trying to "fix it" or guide them away from their feelings (even if we are hurting for them).

We can ask, "How do you think you will feel when you hear/see that sound/sight again? What would help manage that?"

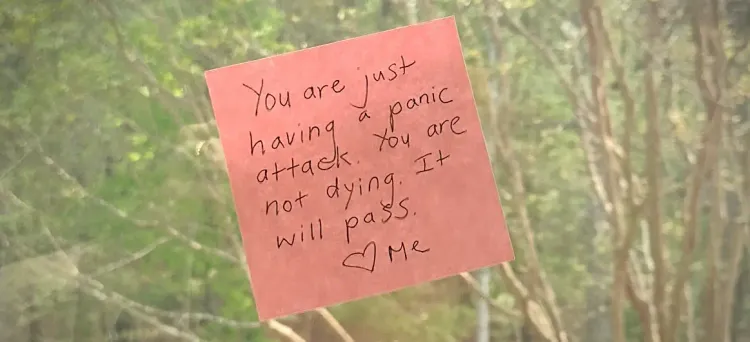

We can explain: "Our nervous systems are designed to register stuff like worrisome sounds and smells as threat signals. When you hear the alarm system being tested, you may feel anxious. That's your nervous system remembering that sound and trying to protect you. Remind yourself that this time, the noise means something different. Be patient with your nervous system as it figures things out."

This kind of reflection allows us to:

1) Cope Ahead - the opportunity to think through how we want to respond to a stressor, and what would be helpful in doing so.

2) Name It to Tame It - Naming or recognizing the connection between the sensory activator and a fight/flight reaction. This awareness can demystify the threat response. It might look like, "Oh yeah, hearing rain is reminding me of when it flooded. That's why my heart is beating so fast."

These strategies help manage the nervous system when faced with a re-activating sensory moment. It might not eliminate the stress reaction, but it can dial it down.

Some kids/teens won't want to talk about it. That's okay too, especially if they are talking to friends or others. The point is to process through it - talking through the experience instead of holding onto it.

More support

If you sense that your child needs more support than talking with friends/family, seek out the help of a mental health professional. They are trained in working through moments of trauma. Certain modalities like EMDR can help release threat from the mind and body. You can find an EMDR-trained therapist or talk with your practitioner about other forms of fear release like exposure therapy or desensitization.

It can be helpful to remember that strong reactions to threats are the mind and body's way of protecting us from harm, just like our ancestors have done for tens of thousands of years before us. Self-compassion, even compassion for human nature, is a powerful tool.

We can say, "Well of course that sound is unsettling. I remember the time I heard that on a truly awful day." And with that simple thought, we are using our Thinking Mind to turn off our own internal siren.