Radical Acceptance: Making Peace with What You Can't Control

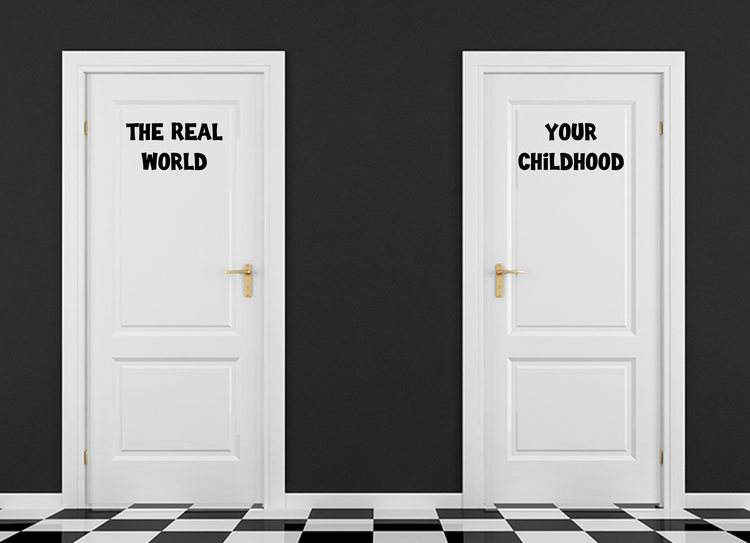

As a parent, one of the most useful coping skills you can have is radical acceptance: Letting go of what you can't control and being okay with that.

Radical acceptance is letting go of the need to control, judge, and wish things were different than they are.

Basically, it's: 1) accepting what you can't control and 2) accepting your emotions around that. It's really about letting go of expectations and accepting what is going on in the moment - even if (especially if) that is intensely frustrating.

Radical acceptance is a coping strategy from DBT (Dialectical Behavioral Therapy), but is has very deep roots that go back centuries in eastern philosophy.

In practice, it might look like this. You have an expectation. Your child has a different expectation.

For example, your child says they want pizza. It's been a long day. You make the pizza, cut it up, and put it on the plate. Now they are refusing to eat it. It's too "tomatoey" (the same pizza they've happily scarfed 100 times before).

- Option A: attempt to persuade, push back, insist, enforce power

- Option B: accept, recognize the limits of your control, breathe, move on

As I'm sure you know all too well, Option A is generally the more stressful choice.

Option B allows you to say to yourself, "If this really matters, we can circle back when calmer heads prevail." In that situation, maybe you tell your child they can have PBJ, but the next day (when everyone is less tired) you circle back and talk to them about the too-tomatoey pizza. That's a good time to talk about expectations and ground rules:

Hey, what happened with the pizza yesterday? Isn't that your favorite?+ If you don't like something I've made, you can eat something else - but you will need to be as independent as you can and clean up after yourself.

Radical acceptance doesn't equal permissiveness, helplessness, or weakness. It's just that sometimes you have to meet your kid where they are (and where they are might feel ridiculously unreasonable).

With kids, radical acceptance can be softened by knowing that whatever the conflict is, it's most likely very temporary. You just have to take a look at the bigger picture and wait it (or them) out. Part of this connects to that age-old wisdom: Pick Your Battles.

In the Seeds is focused on coping, not parenting. I'm not here to tell you how to parent. But productive coping is necessary for productive parenting.

Radical Acceptance can drastically reduce parent stress by allowing you to let go of things that are largely beyond your control, especially if those things don't matter in the big picture.

In a Lesson at Morrow Mountain, Jeremy Markovich tells the story of taking his 7-year-old son Charlie camping - hoping that Charlie would love the experience as much as he always had.

What follows is a tender story of a father sitting in the space between expectations and reality, and processing what to do with that (along with what to do with the "too smoky" hamburgers that his seven-year-old won't eat).

Jeremy admits that he had idealized the father-son camping trip, but he quickly realized that his imaginings were starkly different than the actual outing. He had to get okay with things not being okay. Nothing dire happened. It just wasn't the trip he had in mind (at all 🙄).

The best thing about radical acceptance is that there's a ton of relief in letting go of an unrealistic expectation. With that out of the way, you can find other responses: patience, empathy, laughter, and even joy at whatever unfolds.

The story of parenting is a story of moments. One moment your child is testing limits, pushing back, rejecting something you hold dear, staring at a screen while you're staring at a campfire... The next moment, they delight you with the person they are becoming.

You might even see them circle back (willingly!) to whatever it was that had you both locking horns. That natural cycle is far more likely to happen in the absence of insistence and resistance (those two are often in a tug-of-war).

My own son went camping with his father several times in between elementary and middle school. He mostly enjoyed it, but there were definitely moments that involved compromise and jettisoned expectations.

But then, just a few months ago, that now-grown boy elected to plan and lead a trip on his own, and despite multiple things going very wrong, he had an epic time.

Radical acceptance isn't cow-towing, accommodating, or giving up. It's the wisdom that in a game of exhausting, no-win tug-of-war, you can drop the rope.